When I came to California from Massachusetts in 1968, newly married—to Berkeley, no less—everything was new, everything was dazzling, and little seemed familiar. It was as though I’d landed in a sort of Disneyland replete with regions: UC Berkeley, Frat Land, Physics/Science Land, Flute and Music Land, and Tupperware Land (suburban San Ramon and Walnut Creek to the east).

But all were merely states in a kingdom: California Land of Food. And what food! And all this after a scant year of kitchen experience in a grungy student apartment. Now I was learning to cook in California.

So much about food! An ever-rich conversational subject. Food as political statement–or not bought as a political statement. Food that sprawled, food that I had to get used to, food full of connotations and philosophy. And though this aspect wasn’t entirely new to me, food as the basis of hospitality, of sharing the wealth, and “Oh, you haven’t had that before? Here, try some!” This new food world also included Ordeal by Academic Dinner Party, the best _______(type in your favorite ethnic) restaurant, farmers’ markets, backyard produce, and stained fingers from the tangles of wild blackberries on the hillsides; food that was talked and argued about, the subject of kitchen wall photos and the newest cookbook out, or the latest gourmet fad.

How lucky I was! I can’t possibly do justice to it outside of an entire book, but here are a few standouts from those Berkeley years: sour dough bread, guacamole, lemon butter— and ripe cherries.

Growing up “back east,” I’d never thought much about bread; it was simply the staff of life. We ate what came from the market, white or rye or oatmeal, and sometimes pumpernickel. But you didn’t talk about it. Bread was just basic.

Not so in the Bay Area! Sour dough bread was a thing, for sure. And that wonderful crust! This was bread with real flavor, personality—and I’d never thought to describe bread dough as “sour” before. I loved it right away.

I remember one occasion, however, at which sourdough didn’t work, a student-led vespers service at the Mills College Chapel. No one had thought to pre-cut the loaf and there we stood around a central altar, struggling to tear a beautiful big round of sour dough apart, let alone into small enough pieces for Communion. Worship came to a halt as everyone struggled and pulled—and then we contended with the crust. We all chewed and chewed. And chewed some more.

More manageably I loved sour dough in wedges, as a component of dinner on Fisherman’s Wharf and particularly at Sam’s Grill, an old fashioned “men’s fish restaurant” on Bush Street in San Francisco, a deliberately un-fancy place where the food was (and still is) terrific. I think they actually very slightly overbake their sourdough, for crusts there are dark indeed, and the flavor is tangy, and yes, very sour.

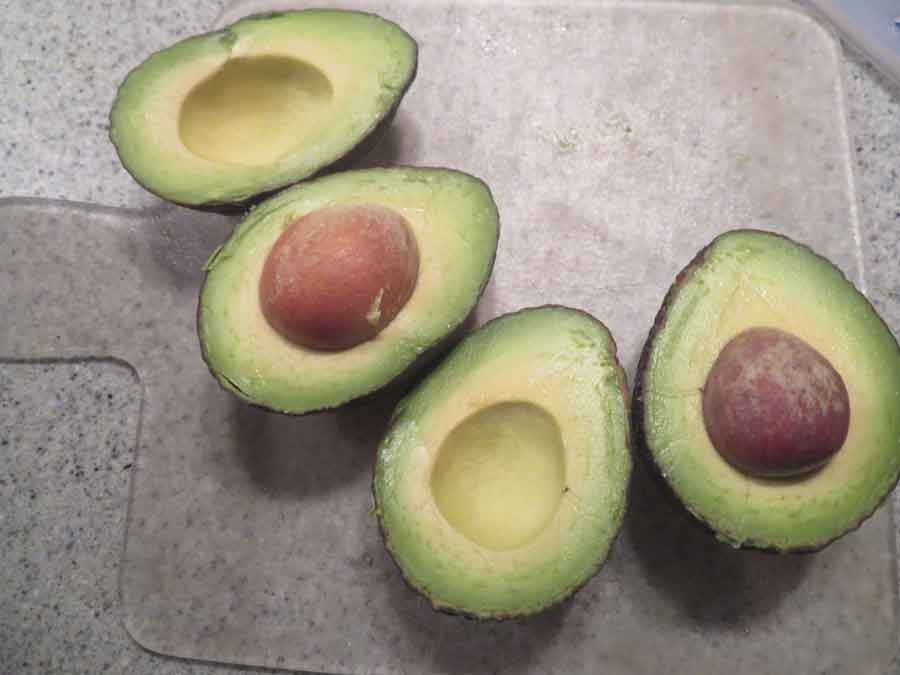

Sourdough bread was part of an occasion, too, when I felt I’d Arrived. With our wonderful next door neighbors, Warry and Howard, as our guests, I served cracked crab on a bed of lettuce, with sliced avocado, Louis dressing, chilled white wine, and sour dough. As we sat down, Howard exclaimed, “Well done, Sally ! You’ve got the combination exactly right! This is The Real California Thing.”

However, if you have plentiful avocados, probably you’ll be making guacamole, too. I’d made guac for Andy, but if you don’t like a thing, you probably won’t cook it well and I was no exception to this. It took an encounter with Al, who was from Columbia, to teach me about guac.

At one of the many parties at Warry’s house, Al appeared with a large bowl of guac in one hand, chips in the other.

I told him, “Oh, I’m sorry, Al, but I don’t much like the stuff.”

He was horrified. Hurt, even. “Oh, but this is terrible! Besides, you haven’t had my guacamole!”

Such a friendly soul, and his handsome smile! I thought, I can’t refuse. “Well, if it’s something you made . . .”

“Oh, up to now, you probably haven’t had real guacamole!” And he shoveled a chip generously through the green glop, handed it over, and said, his black eyes shining. “I put the good stuff in!”

I had to admit, Al’s guac had real personality. “Which means?”

“Oh, a whole lotta lemon, some chiles, onion, all the good stuff. Here, have some more!”

And I did. Warry’s delicious strong margaritas helped, too. But hey, I honestly liked that guacamole. Amazing! By now Al was beaming and we kept on talking until he remembered he was supposed to be passing the stuff around. I can’t now summon the taste of his version but I remember it was spicy indeed. I kept being caught by his smile, dark eyes flashing from a swarthy face, and all the jokes he cracked. Who knows? Maybe what I really needed was to have fun with guacamole, taste it enough times to get used to it, even trust it—or to simply enjoy it while meeting a new friend.

Even before I came, I’d always thought of California as a major source of citrus. Yet I was still amazed when we visited my Aunt Betty and saw her back yard orange orchard. Of course we were sent home with a bag-full. This was the same Aunt Betty who’d already sent me a guide to California style food: Helen Brown’s West Coast Cookbook, which arrived shortly after Andy and I became engaged, with the inscription, “Love and much happiness and good eating.”

I didn’t immediately realize the scope and thoughtfulness of Betty’s gift. Perhaps, too, she didn’t know what a classic that book was even then and has remained. Oddly, now, though, it strikes me as having a distinctly un-California clubby tone with its “we like” or “we serve” observations, but I admire all the history that comes with the recipes. And I remind myself, it’s not just about California, but Washington and Oregon as well; still with the vastness of the Golden State, it was a good while before we ventured out elsewhere, let alone realized (have we ever?) the state’s extent.

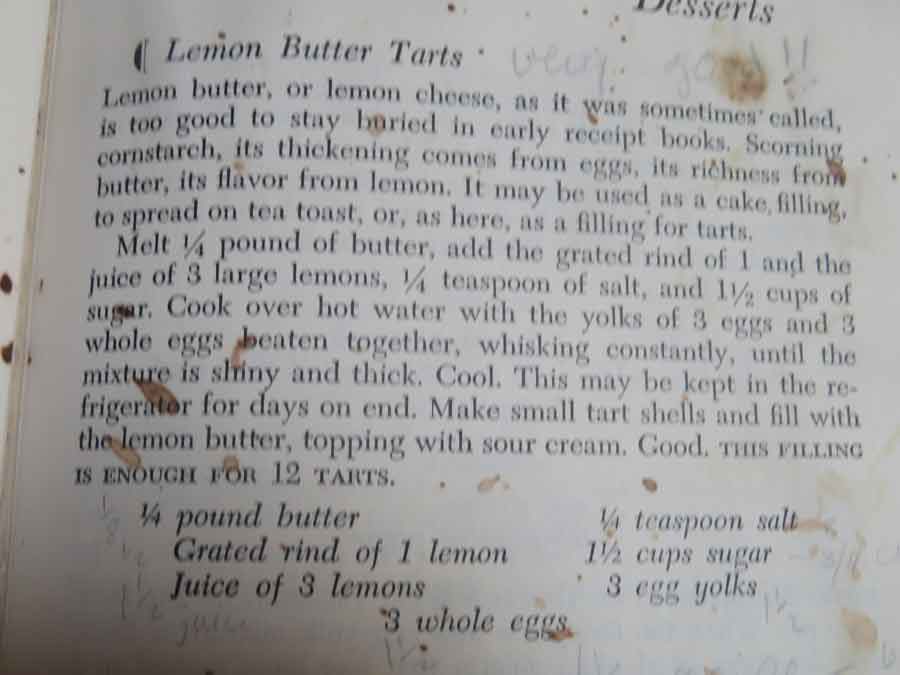

Oddly, though, my happiest use of the West Coast Cookbook, and the most food-spattered page of all, is this recipe. Yes, it is “very good!!” as I scribbled in years ago.

But wait a minute! Lemon Butter didn’t originate on the West coast at all, but is a classic English recipe, often served with scones for tea. It is also sometimes known as “lemon curd” and I’ve seen it commercially sold, too. So this wonderful stuff, like so many recipes and cooking ideas, has traveled a long way.

But wait a minute, wasn’t everything invented in California?! Or just carried here, in someone’s suitcase or bag of cooking tricks, no matter what the origin? It just tasted good, slipped in, and became “ours,” probably. Like recipes all over the world.

What was and is true all over the state was abundance. For me, an early moment defined the generosity of the land. Andy and I were on our way to Marin country, to drive up Mt. Tamalpais, when somewhere in Richmond, I spotted a farm stand by the roadside. The sign read: Cherries, 3 lbs. for $1.00.

“Oh, let’s stop!”

And as soon as he did, I leaped out. Easiest sale they ever made.

Real ripe cherries—and so many of them! I could have eaten the whole lot, though I did share with my husband. And our dollar’s worth was more cherries than I’d ever before had. In my childhood, cherries might appear in Massachusetts stores for perhaps a week, then disappear for the next fifty-one. One year I was so disconsolate that my grandmother ordered canned cherries for me from S. S. Pearce, the specialty grocer in Boston—but they weren’t the same at all.

All this, anecdotes and everything else, is by way of expressing the richness of it all. And there’s an added ingredient: I was living during the “California Food Revolution” of the 70s; life—at least foodwise—was “a bowl of cherries.” Before becoming the foodie mecca of today, Andy and loved taking day trips to Napa; back then it was a sleepy little single-road-through district, except for Robert Mondavi’s bold and venturesome new winery. No charge for tasting, either. Friends drank “their” blend of coffee from the original Peets; I, too, frequented the Cheese Board, which was The Place for that commodity. Oddly I was unimpressed by Chez Panisse and amazed by its later fame. More prosaically I was a member/shopper of the Berkeley Co-op, learned much from its home economists (I still use their cookbook)—but some days, I confess, I fled to Safeway where I could just buy a week’s groceries without politics, opinions, petitions, or orphan puppies or kittens thrust upon me.

The main thing was, I lived among people excited about food and I caught their excitement. I cooked and cooked. I still use my West Coast Cookbook, though leafing through it, I’m surprised at some of the things I tried back then. I still retained some east coast habits, but I became a California cook. And even if the loaf of sourdough was hardly suitable for communion, it was a wonderful symbol of food as welcome. For California offered me a seat at an enormous table and I sat right down and joined in.

Not only did you “sit right down and join in”, you pulled up chairs for guests around a very extensive and welcoming table. I, too, have made lemon curd for decades and I will add here that meringues are the perfect accompaniment. Why? Because those three jiggling egg whites set aside need a recipe, too!

Another good one (a trick in the old cook’s bag) — I bet I’ve served it to you? Buy a plain angel cake, split into layers, spread each layer with the lemon curd and some berries, – assemble, spread the top, too, and decorate with more berries. Delicious! and of course, meringues – what could be nicer?

Delightful, Sally! I was introduced to lemon curd as an under grad at Western Wash. U. in Bellingham, Washington. We girls would take forays across the border to buy lemon curd in Vancouver, B.C. Your descriptive writing always brings joy.

I hope I can serve some to you someday, Marlene! Glad you enjoyed this piece! Love, Sally

I’m drooling🥰

So glad you enjoyed it, Cheryl! Wish I could serve you some of this! Thanks for reading, too — Sally

I’m hungry now.

Lush and beautiful rendition of a happy time. (: