When I first came to California in 1968, newly married, I started right in to continue the Thanksgiving traditions I knew from childhood, though one of my first such dinners included turkey cooked at too high a heat and thoroughly dried out; somehow I cobbled together a lot of gravy and saved the day. I also remember going to dinner at my Aunt Betty’s and having my first ever taste of a wild turkey. (It seemed quite “tame.”) Over the years, though, I’ve mostly cooked at home and invited family and friends to bring food or drink, hoping both to be inclusive and to spread the work load a little.

As I’ve lived here all these decades, California’s bounty has so often given me gifts, that I’ve also come to feel other days of the year as Thanksgivings in themselves, such as an Easter dinner with fresh spring vegetables, cracked crab from San Francisco, or outdoor spreads of local wine, sour dough bread, and cheese.

And once in a while, a single dish will provide, via taste or circumstance, or both, Thanksgiving all by itself.

Almost twenty years ago, visiting my neighbor, I noticed a handsome old platter with a gold border, at the center of her dining table. When I commented, Vera replied, “Oh, that’s usually for the turkey at Thanksgiving.”

Now it was heaped with ripening fruits: apples, mangos, lemons, and nectarines. She went on to say, “I’m getting ready to make a batch of chutney.”

“Oh, how nice! . . . I remember when my mother and grandmother made jams

and preserves when I was a kid.”

A few days later, Vera called and asked, “Would you like to make chutney with me?”

Somewhat surprised but pleased, I said, “I’d love to, Vera!” We set it up. I offered to bring some sandwiches and she said, “Well, if you’re all right with muffins and things, I can offer that.”

I said, “Oh, that would be lovely, thank you! I’ll bring my favorite knives, too.” “

“And would you bring a cutting board? It’s difficult for us to use the same one.” A good practical point.

Vera and I had met several years before on the sidewalk outside her house, she gardening on the banking, I walking our Corgi. At first I found her gruff manner off-putting, and an odd contrast with her English accent, which was still prominent though she’d lived in this country for decades. Trading tales of our heritage, eventually we realized that we were the only people in the ‘hood’ who received This England, a beautiful magazine which my English cousins generously continue to send.

Of course I noticed Vera’s intense blue eyes, amid a face webbed with small scale wrinkles. Often her short gray hair reminded me of Barbara Pym’s character who says, “My hair’s a bush.”

When I arrived for chutney making that morning, Vera was sitting out in the garden in warm sun. Momentarily I regretted going into the dark house but forgot as soon as I saw the set-up. Her kitchen table was covered with old towels, bowls, pans, the recipe on a plastic covered card, the platter of ripe fruit, her cutting board, and space for mine. A roll of paper towels stood ready for each of us, plus the wastebasket between our chairs for peelings and pits. Brown sugar, vinegar, and needed spices were assembled on the counter.

Tying on my apron, I brought out my knives. Vera said, “This recipe is predicated on 6 cup increments of fruit. Now this is a 4 cup measuring cup, so we’ll have to take that into consideration.”

Picking out an apple, I peeled and chopped it, then checked with her about the size of pieces. “Oh, I think a little smaller, those take longer than anything else to cook down.”

The worst job was the mangos: we each did two. “Juicy” was an understatement. However, my serrated blade did a terrific job of scraping the stringy flesh from the pit. The peaches and nectarines were so dead ripe that no blanching was needed to peel them. I went on to onions, then worked over lots of ginger root.

Briefly I glanced outside. The garden was running rather wild, as Vera’s foot had been troubling her lately. Still it was beautiful, though, for her garden was a kind of hidden sanctuary, shady and full of interesting blooms and leaves, also ornaments and handsome rocks she’d lugged back from places.

We talked, though I tried not to chat constantly. I was conscious of this being a lot of intimacy. My usual style was to visit Vera every couple of weeks for an hour or so; occasionally I’d had her over for supper. As we worked, we talked about other fruits, currants, gooseberries, food in general, a recent salmonella scare, and a former neighbor whom we kept worrying over.

The peaches sliced and chopped with perfect ease, the nectarines mostly so. Mangos were so slippery–puddles on the cutting board! Vera noticed my speed with onions and commented, “You must like to cook very much, usually people who work like that, do.” As we went along, we deposited four-cup measures in her big kettle, and though I think she miscounted by one measure, I didn’t correct her. Chutney’s pretty indestructible, and she was in charge.

Finally everything had been cut, chopped and dumped in, stirred into a mottled yellow mixture, with dark spots of raisins for punctuation.

Now Vera set out lunch: a tin of her muffins, some cherry tomatoes from the garden, and a Fontina cheese (very good) with cheerful red wax rind.

“What would you like to drink?” I asked for water, and we sat down with glasses and a container of ice water from the fridge. And the chutney bubbled along.

That whole process “took me back.” When my mother and grandmother made mincemeat, I’d be plumped down on the kitchen stool with a bowl of raisins to separate and de-clump, while Mommy and Grammie did the whole rest of the complex, fussy job. Now it felt good to be a working adult in the process.

Like Vera, only an earlier English immigrant, Grammie assembled a major combo of things: raisins, currants, lemon and oranges (juice and peel) glaceed citron), apples, and a small measure of rum or brandy. Rich stuff! She used mincemeat perhaps twice a year to fill amazing pies for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

A week later, Vera gave me a large jar of chutney, which was simply wonderful. Such a mix of flavors and color and tastes, as varied as her flowers and plants—chutney is a kind of garden in a jar. Vera’s style was Anglo-Indian, a fruit/vinegar/salt medley pf a jam-like consistency, though neither as sweet nor as thick as Major Gray’s. Hers was savory, with a slight pucker to its taste.

I think back now to Vera’s speaking of the big platter: “I usually put the turkey on that at

Thanksgiving.” Really the chutney, the fruit of all those fruits we labored over, is Thanksgiving in a jar, certainly a kind of harvest food.

Though I helped her just that once, I loved the shared doing and talk. We might well have been quilting or preparing an entire great meal. Slicing, cutting, the juices running and staining our hands, we created something that was more than the sum of its parts. Yet all those parts were pretty ordinary things, too.

But one thing is perhaps not so ordinary: Vera told me that she would occasionally stop by the fridge and take a small serving of chutney, as though it were a tonic. I can almost see her standing here, enjoying the spoonful, meditating over the flavors.

So I, too, stop now for a spoonful, a moment of remembering Vera, and giving thanks for our friendship.

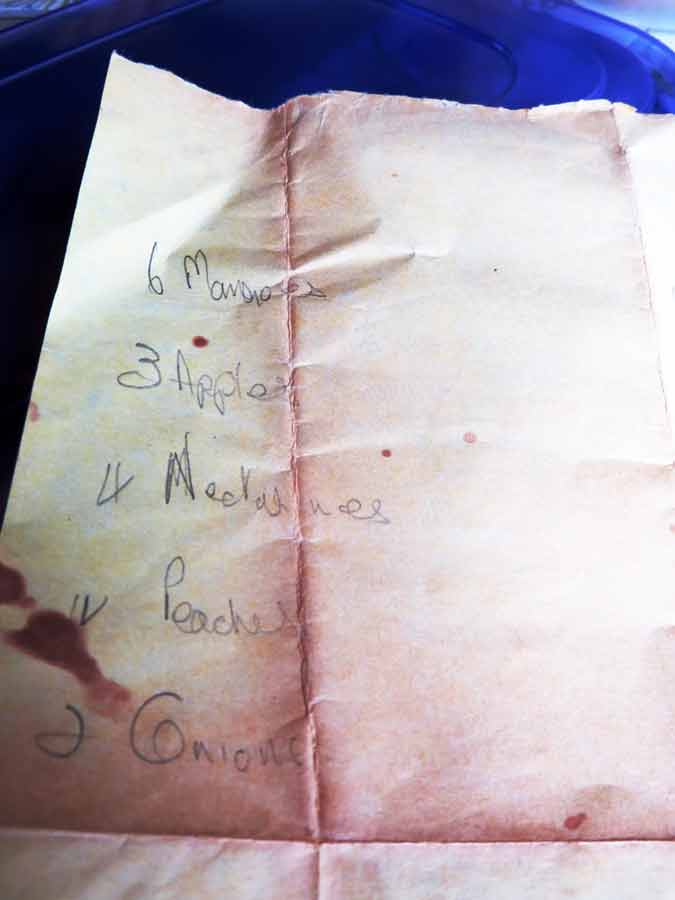

A scrap of paper in Vera’s writing, which might have been a shopping list for chutney.

Lovely as always Sally!!!

Tina, thank you! Happy Thanksgiving to you both!

Charming and calming. A much-needed oasis in the cacophony of words streaming through our times. Ah, exhale.

Thank you, Ann — and I give thanks so often for your kind and thoughtful friendship. Hope you have a lovely Thanksgiving —- Sally

What a wonderful description of making chutney with Vera. Lovely pictures too.

I bet you remember her, Carol? Sending you and David love!

Beautiful piece! I was sitting there with you and Vera, chopping along! As a Scandinavian, I am unfamiliar with chutney. Now I’m curious! Thank you, Sally!

Wish I had some now — and what we buy under that name is rather different. I think it’s a variable recipe, and well, indestructible? Like picallili, or “relish” — everyone’s is different, I think.

Sending you love this Thanksgiving! Sally

Delightful! A tribute to neighborliness, connection, medleys, and making a mess! I offer a title to your still life at the top: “Elevating the Turnip” At least I think I see a turnip in that mix! A plain cousin invited to the fancy relatives’ party!

Yes, definitely a turnip. Of course it didn’t go into chutney but they are to give thanks for, in a good beef stew or turkey soup. Same with onions, I could hardly live without ’em. Yes, very much the country cousins — you’ve got that right?!

From one cook/kitchen operator to another: Happy THanksgiving and all the chopping!

Lovely story Sally..

Thank you, Irene — I hope you are having a lovely Thanksgiving, too — Sending you love!