The Stars and Stripes . . . American Patrol . . . Oh, those great old marches! And the memories that play right along with them . . . National Emblem . . . The Invincible Eagle. . . Semper Fidelis . . .Classics by John Phillip Sousa and his compatriots. As I listen, they summon up a whole parade’s worth of impressions and moods, as though some romantic painting (preferably in an ornate gold frame) scrolls before me and comes to life, full of color and sound and feeling . . . Oh, and I hear still more . . . Washington Post, Independentia, Colonel Bogey . . . Type in the name of any of these old reliables and they all pop up on YouTube.

This year, with Memorial Day upon us, and the Fourth of July close on its heels, I’ve been listening yet again, because every Memorial Day of my high school years, I marched in parades in small towns on Cape Cod.

At the same time, today’s news keeps jolting me. What on earth are you thinking of, Sally? You sound so nostalgic, as if there were no conflict, no division or dissension anywhere, as though your memories expressed the ways things are and should be. They’re unreal, or if they ever possessed any reality, it’s all gone now. We’re living in a different America.

Oh, all right, if you enjoy the memories and love the old marches, yeah, go ahead and listen to them. But keep it to yourself. What good do they do in this world today? What relevance do they have any more?

Perhaps you noticed that I spoke of marching in parades, plural. My school was Nauset Regional, meaning that Nauset educated kids living in Eastham as I did, plus the two towns it was sandwiched between, Orleans and Wellfleet. So every Memorial Day we marched in all three. Though we were no Rose Parade outfit, between uniforms, getting everyone to the starting point and boarding the bus, all our instruments at hand, then twice repeating the process, the whole parade business amounted to quite a production—a kind of progressive musical event.

Seen from the curb, the Nauset Regional Band looked smart indeed: gold pants, black jackets with white trim and “brass” buttons, topped off by black hats with shiny brims. Our outfits were Army surplus, (officers’ uniforms, we were told); both pants and jackets were wool, with a white nylon ascot to fill in the neckline. Looking closely on a warm Memorial Day, you might have said, “Gee, those kids look hot!” And we were. Also, having been dyed in lots, those “gold” pants came in ochre, mustard, bronze, harvest gold, and even a shade close to saffron. En masse, though, you probably wouldn’t have noticed the variety. We all swore, however, that the jackets gained weight as the sun rose.

Just once, we also marched on a sweltering Fourth of July in Wellfleet, where the parade ended at the town pier. Most of us would have happily kept going right over the edge into the water. I don’t know which was worse: that or the one year we played on a frigid Veterans’ Day in November. Oddly, when I remember back, that parade always takes place on a particular block of Main Street in Orleans; Eastham’s is defined for me by a little triangle of road divider, with a commemorative marker just off Route 6.

As Nauset had no football team, Parades were our territory. Our practice sessions took place in parking lots. We marched those parades down main streets or roads, in more or less straight-forward columns—except for corners, which were rather on the haphazard side. I hope now that we looked better than I think. However, we were fortunate indeed not to follow horses, and we had no musical competition, either: For those parades, Nauset was The Band.

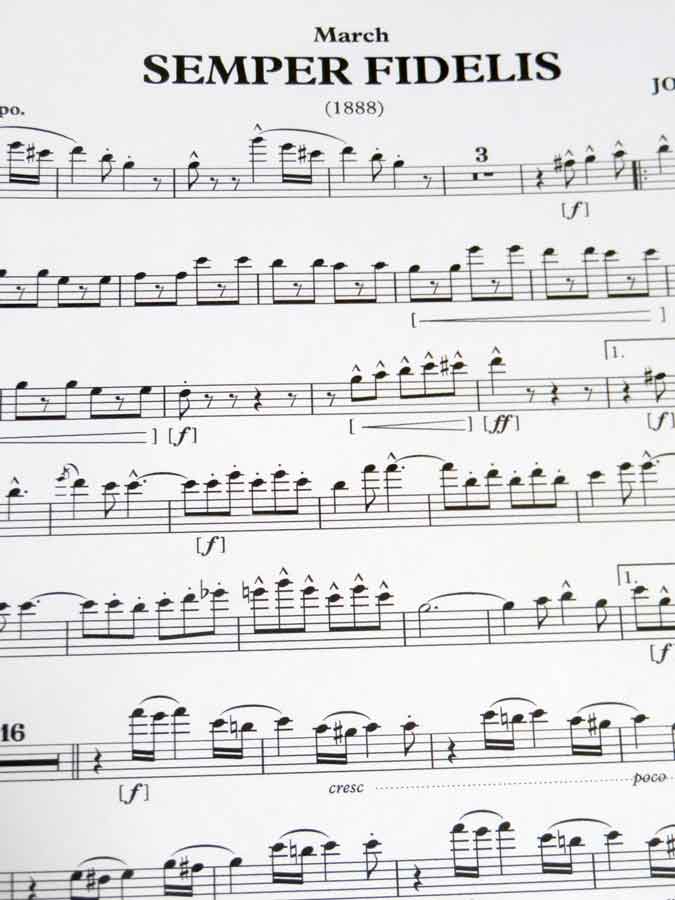

For a flute player like me, there was an added problem: how to carry the music, with arms and hands already occupied. The solution? A “lyre.” This was a wooden wand about 20 inches long, curved at one end to clamp under the left arm; from there the wand straightened out and ended at a vertically mounted clip (in lyre shape) which held march books five by eight inches. Altogether, between the heavy uniform jacket with its braids and trimmings, the shiny-brimmed hat, my flute, and the lyre clamped under my arm, I sometimes felt as though I’d been installed in a kind of musical traction.

Thus hooked up, what was playing in my mind? Excitement at being part of the occasion, at the fanfare, the celebration of it all. People enjoying our music. Occasionally I’d spot someone I knew and they’d wave, though I couldn’t wave back.

Mostly I focused down on playing for marching was work. I spent most of the time pushing out notes. I also literally watched my step, noticing when anyone around me veered or took large, random catch-up lopes to round a corner. Due to the flute’s sideways position, I also worried when we hashed up a turn or had to constrict our ranks in a narrow street.

Sometimes it felt as though the pavement itself propelled me, though really, once we started, I was carried on a friendly conveyer belt of sound and spirit and drumbeats. I felt for my friends on percussion and when the street beats got ragged, I knew they were getting tired. Yet I loved all the soaring melodies, and especially what I now think of as the brass’ “asides” —those short downward comment phrases in the trombones and other brasses; it was as though the composer had asked to them musically nod in agreement, rather as though our favorite uncles were cheering us on: “Yeah, that’s it! Play it again, guys!”

However, you’d barely have heard me. Generally, the important themes, what you hear and notice, are scored for brass or the louder woodwinds like clarinets and saxes; the flute section mostly supplies musical flourishes and little doodly comments. Then, too, our band was hardly the caliber of the highly trained groups on recordings, where various instrumental sections are featured while others yield the aural spotlight.

At some point in each parade, thank goodness, we’d halt and could rest tired lips, if not our feet, for a formal remembrance. Those earnest ceremonies included an invocation, salute to the flag, perhaps a speech, and a reverential gun volley by several veterans, the shooting usually a bit ragged. At the end, Taps, played by trumpeters Steve or Bruce, one of whom had earlier clambered off into woods or trees to supply the required echo. One year we awkwardly marched into a local cemetery where the ceremony included a petrified fifth grader reciting the Gettysburg Address, frequently and audibly prompted by his teacher from behind a tomb stone.

Poor kid, he was a piece of the Norman Rockwell aspect of it all. Along with green trees along the roads, august New England houses and churches, glimpses of blue water, people celebrating together outdoors, and those patriotic marches.

As for the serious emotion and remembrance invoked by Memorial Day, though, I was about as affected as the small boys who always dove for shot gun shells after those salutes. I was too young, too happy. It was just a holiday, and a signal that school would soon be over. Summer was on the way!

Probably in those optimistic late fifties and early sixties, it took adults to appreciate Memorial Day; World War II seemed “long ago and far away.” Like the parents of my friends in band, and people in town and at school, my parents had served in the war; lucky for most of us that they’d come back. No one ever talked about it, even though many in the crowd must have remembered the years of distant battles, anxiety, rationing, bad news, and lost friends and family members. Our parents and elders had been young once, too, and in their turn, had probably been as untouched as we were. Maybe we were playing out classic adult/youth roles.

Those marches we played, especially the lyrical Trio sections (these usually came last) and their nostalgic melodies evoked a sense of order and “all’s right with the world”—also the sense that we Americans are noble, of good heart. If we played this civilized, controlled music well, surely the world would also run smoothly, people would act nobly and kindly. Our country would.

And now I write in May 2024, with my country in a kind of civil war: bitterly divided over opinions and issues that are mean, sharp, and often irrational. “State’s rights” are still an issue, but with no clear Mason-Dixon line; rather the states and their political climates, are divided within the U.S. in a kind of locational mix.

That regional school I attended, which still flourishes on Cape Cod, seems like a wonderful model, the way we were all equal within it; in theory and during my years there, all local citizens supported Nauset’s ongoing existence and shared its gifts.

As for my naivete, which now seems to me so simplistic, foolishly nostalgic, perhaps I should be patient with myself. I was living in a different time and that was “the beat” then; now the line and pace of march is nowhere near as clear. History piles forward and I find myself out of step, in sharp disagreement with what looks like half the country. I hope that the forward march on which we’re carried, changes and calms, and that someday, once again, I (and all the rest of us) will feel happier, less riled by events and people and news. Maybe America will come through and proceed more peaceably once more.

So that my memorial to those past Memorial Days in the band, is allowable, perhaps even valuable, as a reminder that I once felt that way, quite naturally.

In that time and place.

As always Sal, LOVE your perspective! Tina

Tina, Thank you so much for your support — I greatly appreciate you! Sally

Sally, you elicit memories of my own high school marching band days. I hadn’t thought of them in so long and you prompted a fun revisit.

Marlene, Forgive me, I can’t remember which instrument you played — knowing you were mainly a pianist, I connect that with you. Those were good days, though, weren’t they? Sally

Being from New England, this reminds me too, of our town parades that we all took for granted. Beautiful memories rekindled Sally! Thank you..🇺🇸

Irene,

I bet, like me, you remember all the green trees along the roadside –I rather miss those! Thanks for reading — Sally

Sally, thank you for the visit to a calmer place and time.

Helen,

You’re welcome — and it sure was a calmer time then. However, the parades continue, thank goodness. I saw some photos of a Cape Cod parade on FB this morning and it all felt so familiar. Good memories. . . Thank you, friend — Sally

Sally do you remember the gazebo/bandstand at Lake Merritt when we were Mills students? Ron and I would go nearly every weekend to hear the band play. You brought back memories! As an organist, I have never played in a marching band… the thought of that makes me LOL! ❤️

Lynda,

I never actually went there, I’m ashamed to say. Wish I had! I went rather in the opposite direction, played in the Richmond Symphony. Now, there’s a piece I should write — we once did The 1812 outdoors in a park, replete with cannons firing! What little professionalism I had at the time vanished when I heard the cannons fire — I got struck by a fit of giggles and could hardly play.

On the other hand, you’ve experiences I never did, either– I’m sure the organist’s life presents many opportunities a flutist never has. For sure, you’ve outdone in general splendor! Sally

One of the local vets posted on a local Facebook page today that he wanted to see pictures of families having fun, cheering, relaxing…that that was important to him to see. So, perhaps, dear Sally, your high school band was just what some vet needed to see then, too. Not naivete, but promise for the war weary that the effort is worth it.

That’s a lovely thought, Ann — and I’m sure it’s true. I still find it sad that we didn’t know any of the stories. I heard a bit from my father, but as he served in Calcutta, India, he had an “easy” war in a sense – however, as long and lonely as I think all those service people were. But that’s a whole other story, which I may someday write.

Thank you for the insightful comment, an aspect I’d hadn’t thought of. Sally